The following is a guest post from Ben Carlson at A Wealth of Common Sense. Ben writes about personal finance, investments, investor psychology and using your common sense to manage your money. If you’d like to write a guest post, check out our guest posting guidelines.

Don’t Try to Predict Interest Rate Movements

There is one recommendation that I received early in my wealth management career that has served me well: do not try to predict interest rates. There are way too many moving parts involved. To predict interest rates you must try to decide whether we will see inflation or deflation (rising or falling prices).

There is one recommendation that I received early in my wealth management career that has served me well: do not try to predict interest rates. There are way too many moving parts involved. To predict interest rates you must try to decide whether we will see inflation or deflation (rising or falling prices).

You must also try to gauge how the market is pricing in future inflation or deflation. Supply and demand for credit investments also play a role.

Central bankers around the world are keeping short-term rates low and making purchases in other parts of the bond market. There are a lot of factors to consider. Even if you can predict the direction of rates you could still get the timing wrong and lose money in the meantime.

Rates Are at All Time Lows

But with rates at or near all-time lows (in the history of interest rates!) investors have become increasingly concerned with what happens to their bond portfolio when rates do eventually rise. And these investors have a right to be worried. At some point the money being pumped into the global markets by central bankers will take hold and inflation or rotation out of low yielding securities will cause interest rates to rise.

Once rates rise, income producing assets will suffer price losses. This is because bond prices and interest rates are inversely related. So as rates rise and investors are able to get higher rates in the market, the bonds you hold will fall in price to make up for the yield difference.

This makes a lot of income seeking investors nervous, especially those that need current income to fund their spending needs. The perfect way to play the rising rate environment will only be known in hindsight. If you had tried to predict the turning point in interest rates or the bond market in the last few years you would have been sorely disappointed by the fact that rates have continued to fall.

Even though you shouldn’t try to predict the rise of interest rates that doesn’t mean you can’t make some changes to your portfolio to be ready for the time when rates do rise and inflation kicks in.

Historical Interest Rates

They say history doesn’t repeat itself but it often rhymes so let’s look back at the last time we had a rising rate environment to see how things played out. We have to go all the way back to the 1950s, 60s, and 70s since rates have been on a decline for a very long time. This is a graph of the 10 Year U.S. Treasury rate from 1950 to the present:

As you can see there was a steady rise in interest rates during the 1950s and 1960s. Then in the 1970s, inflation really took hold. The Fed Funds Rate was ratcheted up by Fed Chairman Paul Volcker to try to subdue the threat of hyperinflation and he was successful but only after interest rates hit double digits.

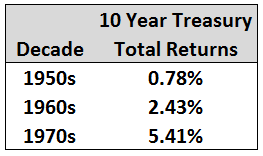

You would think returns on bonds were destroyed in this rising rate environment. Actually, they weren’t that bad. Here are the annual returns by decade for 10 Year Treasuries during this period of rising rates:

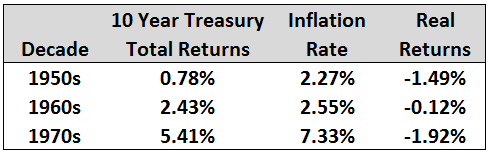

Does that mean that rising rates don’t hurt bonds because returns were not that bad? On an absolute basis, these returns were positive. And the largest annual loss in that time was only about 5%. But if you look at the inflation rate over this time period and see how it affects your real returns, you can see how bonds are really hurt by rising rates.

I’ve added the annual inflation numbers (measured by CPI) over those same decades and the corresponding real (after-inflation returns) of bonds:

You can see how a combination of rising inflation and rising interest rates led to a loss of purchasing power if you were holding bonds during this time frame. After inflation in this 30 year stretch you actually would have lost about 30% of your purchasing power by investing in bonds (stocks were hurt by inflation in the 1970s as well, but they did much better in the 1950s and 60s).

Rising rates don’t necessarily hurt bond returns that badly. You could still use bonds as a way to reduce volatility in your portfolio, just with lower returns than we’ve seen recently.

Inflation is a real problem. The reason bonds perform poorly with rising inflation is because your fixed interest payments are worth less and less over time as purchasing power is eroded. But it’s not like a stock crash where large losses happen very quickly and you have no time to react. It happens slowly over time and eats up your returns in small chunks.

After the difficult 1950-1980 period for bonds, we have seen rates on a downward spiral with only periodic and minor setbacks along the way. Returns in the 1980s for bonds were almost 12% per year and in the 1990’s and 2000’s, they gave you a yearly return of over 7% and over 6%, respectively.

How to Proceed With Rates So Low

Now that you have this information, how can you use that to protect your investment portfolio? Just because I think you should not try to predict interest rates does not mean I think you should ignore them altogether. Investing requires us to weigh probabilities to make decisions based on what we have seen in the past but with an unknown future ahead of us.

1. If Rates Rise

If rates rise, the longer maturity bonds (20-30 year maturities) will get hurt the most. So you should stay away from longer dated bonds. That’s an easy one. Rates could continue to go down and they might, but they can only go so low.

2. Rising Inflation

Historically, in a period of rising inflation, inflation-linked bonds, emerging market bonds, and commodities tend to do well. If we are in a period of rising economic growth but inflation stays under control, stocks, corporate bonds, emerging market bonds, and commodities have done well in the past (this would be the last four years or so).

3. Falling Inflation

With falling inflation, stocks and government bonds usually perform the best (again this has been present the past few years). And in a falling economic growth environment, inflation-linked bonds and government bonds have done the best.

The best way to plan for a potential rising rate environment is to have a diversified portfolio of bonds across different geographies and asset type. You can also use a laddered approach by blending short-term and intermediate-term bonds to decrease your interest rate risk.

Conclusion

Since it’s impossible to predict how things will play out with the global economy it makes sense to have all of your bases covered. It would be great if you could put the perfect portfolio together at just the right time when rates rise but that will be nearly impossible.

You can minimize your risk by spreading your bets and having a diversified asset allocation plan in place. You can also lower the maturity of your bond portfolio and have inflation hedges in place if rates ever do shoot upward.

Just don’t try to reach for yield and use stocks in place of your bonds in search of extra income. Reaching for yield can lead to increased risk in your portfolio.

Subscribe

If you enjoy receiving the Dividend Ninja in your mailbox, don’t forget to also subscribe to the Dividend Ninja Newsletter. Thanks for reading!

Since I believe in stocks (mainly the dividend paying stocks) I tend to say, “Who cares about bonds”!

I do not invest in them because I believe that compared to the stocks at the end of the holding period your dollar values is nominally same as it was at the time you purchased the bond (unless purchasing under par) and interest is way less than dividend you can get with stocks.

My stock portfolio is currently growing at 13% per year plus receiving 4.7% annual dividend. How can bonds beat this?

Bonds can serve a purpose in periods of economic uncertainty and lower your drawdowns. They were basically the only asset class that was positive in 2008. You are right that over the long-term investors are usually better off with stocks (and it’s hard to argue that going forward with rates so low).

But the main function of bonds in a portfolio actually has to do with controlling the irrational behavior that investors show from time to time. They allow you to rebalance your portfolio in times of uncertainty. Bonds are basically an anchor to keep investors from bailing out of stocks at the wrong time and selling at the bottom or jumping in at the wrong time by buying at the top.

If you have a process that allows you to rebalance and stick to your dividend stocks through the inevitable downturns then you may be right that you don’t need bonds in your portfolio. But for most investors they need the stability that bonds can provide to make sure they are able to be successful in the long-term.

Ben, it really depends. I might agree with your explanation, but I do not have experience on that. I am a long term investor holding for another 20 or so years. So looking at 2008 drawdown makes no sense for me. The stocks fell incredibly down and although I was scared I was buying. Three years later we are higher than we were before the crash. Counting in the dividends I received I had no need to protect my portfolio by selling stocks and moving into bonds. Not even talking about bad timing which I have never figured out, so instead of selling stocks at levels with a loss and buying bonds in expectation of further stocks drop I would rather prefer staying in stocks, riding the downturn and see my account recover. And if it won’t recover, it doesn’t matter to me, because it is the income stream which is important, not the balance. If the company cuts the dividend, then I am selling, and not because some investors out there are freaking out.

And also that stability you mentioned is no longer a valid reason and it is a misconception as recent studies proved. When the interest rates were set free in late 70s (in 1978 FED decided to let the rates float), the volatility of bonds became as volatile as stocks. So there is no stability in bonds anymore.

I agree with you that those who can stick it out and buy during panics will do very well for themselves. Buffett said that cash combined with courage in a crisis is priceless. I’m a long-term investor as well and buying in ’08 was hard to do but I knew it would make sense over my longer time horizon.

But it seems like 90% of investors don’t understand this. Almost $1 trillion has poured into bond mutual funds in the U.S. since ’09 while stock mutual fund flows have been negative (go figure). So bonds investors need to be aware of the risks of investing at such low rates and how it will affect their portfolios. Most bond investors have never had to deal with this. Since the mid-1970s the BC Aggregate bond index has only had two negative calendar years and the largest loss was 3% or so.

So you’re right that the volatility going forward will be higher than it’s been in the past but bonds will still not face the large drawdowns that stocks can have in very short time frames. This will matter the most to retirees that will need to take distributions from their portfolios. In a dividend portfolio the only time this would matter would be if your spending needs were greater than the dividend yield.